Illegal Here, Legal There: Alexander Kirk’s Journey Through Cannabis Criminalization

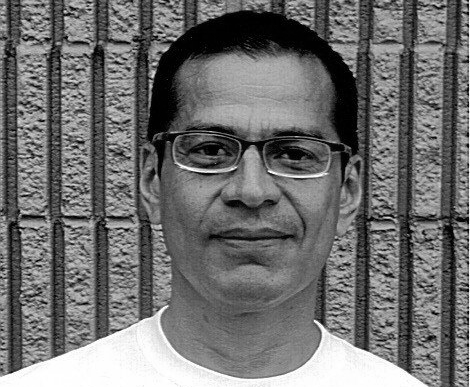

When Alexander Kirk walked out of prison on December 10th, he stepped into a world that had shifted beneath his feet. But the shift wasn’t universal. In Iowa, where he lives, cannabis is still fully illegal. Drive two minutes across the bridge into Illinois, and that same plant, once the root of his decade-long incarceration, is not only legal but a booming, billion-dollar industry.

That contradiction sits at the center of Alex’s story.

He’s a father, a mechanic, a reader, and a deep thinker. He’s also someone who spent more than ten years of his life behind bars for the same substance that dispensaries now sell with flashy packaging and tax revenue incentives. “It’s crazy,” he says. “One side of the bridge is legal, the other side isn’t. It’s hard to believe.”

A Life Interrupted

Alex’s most recent sentence—ten years in federal prison—started with a bust that was as much about timing and proximity as anything else. He was on federal probation for a previous cannabis offense. A raid at a residence he didn’t live in, but where his truck was parked, ended with a federal indictment. A tip from his child’s mother, who was angry about a disagreement over vacation plans, helped open the door for the investigation. “She made a call, gave them a tip,” Alex recalls, without bitterness, just clarity. “And that’s all it took.”

The charges? Conspiracy to distribute less than 50 kilograms of marijuana—a charge that, while less than the quantities tied to large-scale trafficking operations, still carried weight under federal law. He received 80 months for the new charge and another 40 months for violating parole.

The math added up to a lost decade.

“I had already done ten and a half years the first time,” Alex says. “I was institutionalized. Prison became familiar. It’s where I knew how to move.”

But even when you know the rules, prison isn’t easy. The hardest part for Alex wasn’t the food, the routines, or the guards—it was missing his children growing up. “I got five kids. Three of the older ones talked to me after and explained how I chose the streets over them. That was hard. But it was true.”

He reflects on it now with a kind of painful honesty: “I didn’t want to pay for weed, so I started selling it. I smoked, and I hustled. Eventually, it got out of hand.”

Knowledge Behind Bars

Alex didn’t spend his time in prison passively. He worked in the prison garage, learning to fix cars—something he’d loved as a kid. He dove into books and self-help titles. One that stuck with him wasThe Voice of Knowledge by Don Miguel Ruiz. “That one changed things,” he says. “It helped me realize everyone’s got their own story they’re telling themselves. That helped me stop taking things so personally.”

He also began thinking about the world beyond prison. He drafted a business plan for a youth program designed to keep teens from ending up like him. “I wanted to show them they had options,” he says. “You don’t always get that when you grow up in survival mode.”

The Politics of Legalization

What’s jarring about Alex’s story is not just the sentence—it’s the fact that it happened while the national conversation around cannabis was changing rapidly. By the time Alex was halfway through his sentence, multiple states had legalized recreational marijuana. Billion-dollar brands were being built. Politicians were posing for ribbon-cuttings at dispensaries. Celebrities were launching product lines.

And people like Alex were still behind bars.

“It’s unjust,” he says bluntly. “There’s no reason someone should be locked up for weed while companies are out here getting rich off it. The little guy got crushed. They legalized it after locking us up, but didn’t let us out.”

The irony was never lost on him: that he was doing hard time for something that was now a tax revenue stream in neighboring Illinois.

A Second Chance and Real Support

Alex’s sentence was reduced under the First Step Act—a federal law aimed at correcting some of the harshest penalties in the justice system. Thanks to that and a longer placement in a halfway house, he was released earlier than expected.

Through a friend, he reconnected with a woman from his past who introduced him to theLast Prisoner Project (LPP). At first, he was skeptical. “We never heard about people helping folks like us. I didn’t think it was real.” But he gave it a chance—and found not just advocacy, but consistency. “Even getting emails, updates, hearing from people… that helped. It made me feel like someone gave a damn.”

Through LPP, he learned that he qualifies as a social equity candidate in states with legalization programs. That means access to business licenses and support that could help him transition into the legal cannabis industry. He also learned he might qualify for early termination of his probation—a process he’s now pursuing.

“I want to get into the legal side,” he says. “I know the game. I lived it. Now I want to do it right.”

Life After Prison

Alex is currently working in the halfway house kitchen. He’s trying to stay grounded, focused, and patient. Reentry is never easy. “You come out and everything is fast. You feel like you’re behind. But I remind myself: it’s not a race.”

He’s rebuilding relationships with his kids. He’s focused on starting a business—maybe something in cannabis or something with cars. He hasn’t fully decided, but he knows he wants to help others, too.

“There’s still a lot of people inside,” he says. “And they shouldn’t be. Not for weed. If we’re really gonna legalize it, let’s legalize it for everybody. That means letting people go.”

“Get to Know Their Story”

Alex doesn’t want pity. He’s not asking for a handout. What he wants is what most people want: a chance to live free, to work, to be with his family. To matter.

“Just because someone’s been to prison doesn’t make them violent. Doesn’t make them a bad person. Get to know their story.”

Alex’s story is one of transformation, not because the system rehabilitated him, but because he did the work on his own. Now he wants to use his experience to change the system itself.

He’s already started.