A Journey of Redemption and Cannabis Advocacy: Q&A with Matthew Nicka

A Journey of Redemption and Cannabis Advocacy: Q&A with Matthew Nicka

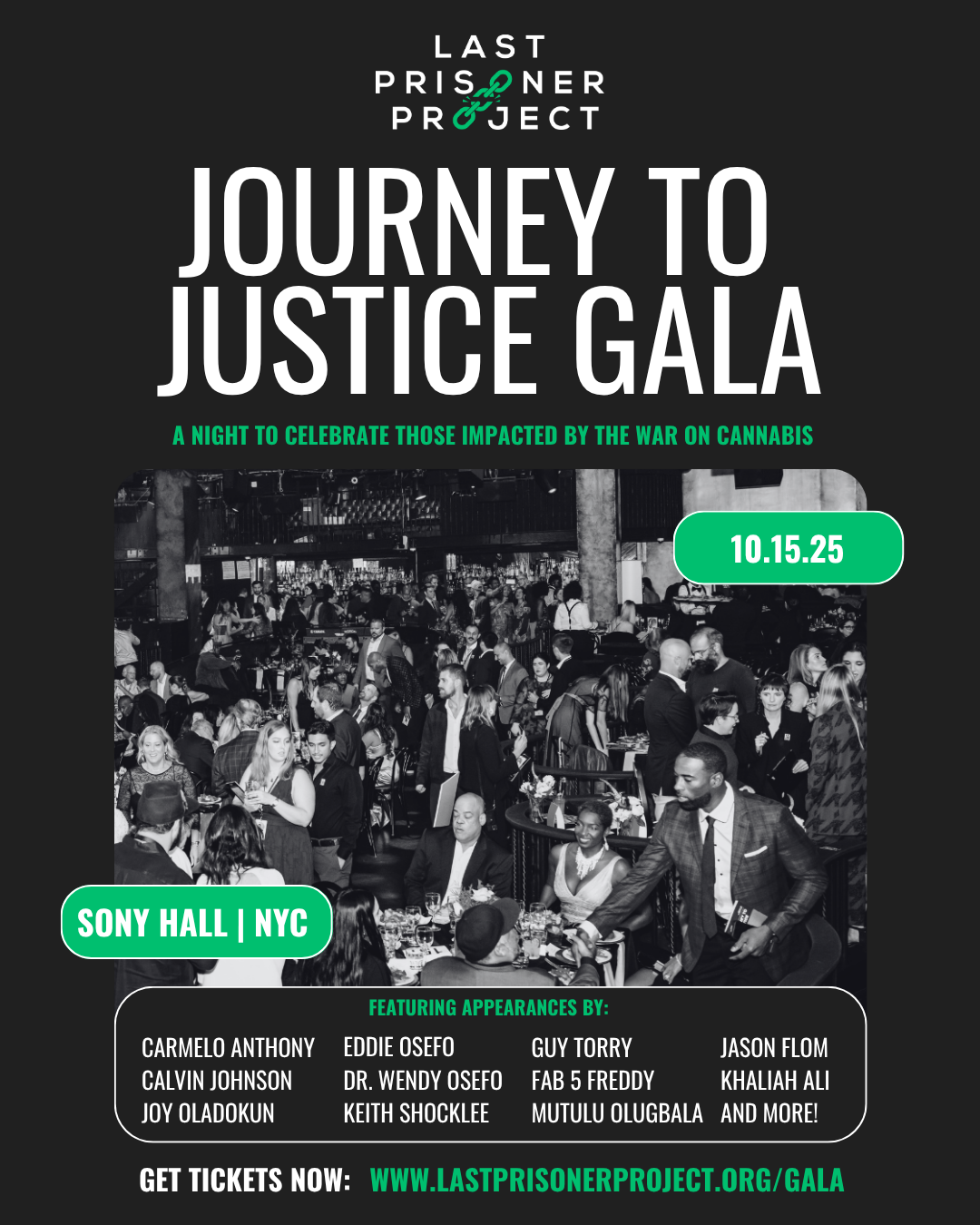

Matthew Nicka's journey of growth, incarceration, and reintegration into society after serving a 15-year sentence for a non-violent cannabis offense is both a poignant and eye-opening story. In this exclusive Q&A with Stephanie Shepard, the Director of Advocacy at the Last Prisoner Project (LPP), Matthew sheds light on his background, his arrest, and his experiences before and after incarceration.

Matthew's story highlights the need for reform in the cannabis industry and the criminal justice system. He was a non-violent cannabis offender who found himself sentenced to over 15 years, serving nearly a decade of that sentence. The stark contrast between his life before and during incarceration underscores the impact of institutionalization and the challenges faced by those reentering society.

Despite the hurdles he's faced, Matthew's determination to reintegrate and contribute positively to society is evident. His short and long-term goals, which include education, career growth, and spending time with his family, showcase his commitment to building a simple, fulfilling life.

As the cannabis industry continues to thrive, Matthew's journey serves as a powerful reminder that criminal justice reform and the release of non-violent cannabis prisoners are essential steps toward a more equitable and just future. His experiences also emphasize the importance of organizations like LPP, which work tirelessly to provide support and advocacy for individuals like Matthew who have been affected by cannabis-related convictions.

Through Matthew Nicka's story, we are reminded of the significance of compassion, understanding, and the need for change in the face of a system that has disproportionately impacted the lives of non-violent offenders. His journey of redemption and cannabis advocacy is a compelling call to action for a more just and compassionate world.

Q&A:

Stephanie (LPP): Matthew, tell me a little about yourself, your background, and how you ended up speaking with me today.

Matthew: I am a white, middle-class suburbanite from Tulsa, Oklahoma. I grew up with a drug problem. I was 17 years old when I got sober, around 1987. Shortly after that, I discovered the Grateful Dead. I consider myself a wrestler, a deadhead, a sober alcoholic, and now, a convict. I started following the Grateful Dead, and I have always been a cannabis user, so I started to believe in the things I learned on the Grateful Dead tour. We lived outside of society and believed that a person can do what a person wants to do, and if a person wants to do what society would deem “harm themselves”, it’s their right to do so. I’m seeing people freely using marijuana and not hurting themselves. At some point, I began to sell it.

Stephanie (LPP): Can you tell me about your arrest that resulted in your incarceration?

Matthew: I sold marijuana until 2010 when I was indicted for conspiracy to traffic over 1000 kilos of marijuana. I plead guilty to that, as well as to money laundering. As part of my plea agreement, I would not cooperate. I bucked the system the whole way.

Stephanie (LPP): Sentencing is one of the most difficult aspects of the whole situation. How long was your sentence?

Matthew: I plead guilty to no less than fourteen, no more than nineteen years. My pre-sentence report recommended that I should receive 12 1⁄2 years. The prosecutor wanted to give me 33 years. I couldn't understand why. I’m vehemently opposed to firearms, violence, and hard drug use. It may sound like an oxymoron because marijuana is a drug, but I never saw it that way. I don't agree with the terminology of marijuana as a “drug”, but it doesn't matter what I agree with because the U.S. Government considers it a drug. I was eventually sentenced to 188 months, but it ended up being 203 months because I spent 15 months in a Canadian jail that the BOP didn't count.

Stephanie (LPP): I know my first year of incarceration was unbelievably challenging. How was your first year?

Matthew: That was a rough year. I’m not one of these in-and-out-of-prison guys. It was a tough adjustment period. I’m a non-violent hippie, and I have strived my entire adult life to get away from the person that I once was. Before finding the Grateful Dead, I was a violent guy, I didn't treat people correctly. I had no karmic boundary at that point in my life, but the Grateful Dead community showed me a different way. Growing up in Oklahoma, racism was prevalent. I had gotten that upbringing completely out of my system.

Stephanie (LPP): How much time did you ultimately end up serving and how did you end

up coming home early?

Matthew: I served 9 years, 8 1/2 months of a 188-month sentence. I was released under the Cares Act. A good friend of mine, Erin Cadigan, told me she knew of these people who were helping non-violent cannabis offenders get out of prison. I said, “Well, I’m non-violent!” I turned in the necessary information to Erin and she got back to me saying that LPP couldn't approve me because of a violent charge in my past. I knew the 1992 misdemeanor assault charge was showing up despite it being 29 years prior. I was determined to work on that, and Erin lit a fire under me to get the assault charge expunged. As a byproduct of my trying to qualify myself for assistance from LPP, and by them motivating me to get the charge expunged, I became eligible for the Cares Act. It all happened very fast. March 21st, 5 years before my scheduled release date, I’m home, at my mom's house in Florida. Erin put me in contact with LPP's Co-Founder. After we had that conversation, I received a $5,000.00 reentry grant to re-establish my life. I didn't ask for it. It was crazy, but I told them I didn't want it, to give it to someone who needed it more. They wouldn't take no for an answer and made some good points about why I deserved the help. I used the money in the best way possible; I sought out a therapist. I am institutionalized. Prison changed me. I was a mess and the therapist was a way

to help me reintegrate myself back into society.

Stephanie (LPP): It is unfortunate that something as a minor misdemeanor so long ago was still showing up on your record and hindering your life. People do grow, and you grew into an adult who was adamant about non-violence being a key pillar in your life. Did you feel labeled with your charge?

Matthew: It is very easy to be seen as a violent “drug dealer”, but people have a hard time seeing you as a non-violent dealer. Being a part of what the “kids” call the legacy industry, we chose to sell less for the money and more for our beliefs. I didn't need a firearm. I’d go meet clients at the Starbucks, throw a big duffle bag in their trunk then sit together and have a cup of coffee. I’d probably front it to him and I knew he’d honor the deal. That’s what made the marijuana world different from any other drug sales. No one was being harmed by what I was selling.

Stephanie (LPP): When you speak of being institutionalized, what changes do you see in yourself before and post-incarceration?

Matthew: I have a picture to share with you of me and keyboardist, Merle Saunders. Merle was a good friend of Jerry Garcia and a Black man. I was 28 years old, happy, with dreadlocks and a big smile on my face, hugging Merle. You can see on my face, the effect prison had on me. You look at me, a non-violent drug offender who comes into the system, who’s happy and thinking along the right path, and by the end of it, I look like a monster. I wasn't a monster, but you can see the pain and institutionalization in my face. That picture speaks a thousand words.

Stephanie (LPP): It took you many years to escape the negative thinking patterns that you grew up around, just to end up back around those negative forces in prison. How do you see that impact your life today?

Matthew: I still feel slightly incarcerated. I live in a home with my mother, my father passed away while I was in prison. I don't get out very often, but when I do, it’s sometimes overwhelming. When someone asks me what I want from the store or what I want to order to eat, I have all these options, I just have to have them order for me. I find myself going to Walmart and picking the same products we had on commissary because the decision-making process is too much. I haven't truly been able to enjoy the little things yet. I still have my ankle monitor on for 4 years, but I’ll take the trade.

Stephanie (LPP): It’s mind-boggling that you are free to walk around with nothing preventing you from committing a crime besides a little box on your ankle. How do you reconcile that this is a condition of your release?

Matthew: There are two ways to look at it; one, the system is set up to deter others from breaking the law and for public safety, but also, I employ many people. It takes the staff at the halfway house to monitor my device, the case managers, unit managers... the BOP is a business. I do not want to get on a pity pot, I was caught breaking the law, and I knew there would be consequences, but no one deserves a 17-year prison sentence for selling marijuana. I understand their job is to lock people up and my job was not to get caught, and I got caught. The prosecutor did better at their job than I did at mine in that case.

Stephanie (LPP): Since you’ve been home, can you describe what it’s been like for you to reconnect with your family and friends?

Matthew: I was shell-shocked. One great thing was I was able to go to AA often and re-connect with a lot of my old friends both from my hometown and the Grateful Dead world. I stayed away from everyone while I was going through my stuff because nobody wants those issues. When I got home, a lot of people just showed up to visit me out of nowhere. It was incredible. There are a lot of people who believe in what we’re doing and know that I'm not the monster that the U.S. Government made me out to be. They came and showed me support. Acclimating was hard for me because as I said, I'm very institutionalized. My mom might say “Let’s watch this show together.” and I say “Mom, you know I work out at 1:30, and at 4:30, I run.” I don't eat until after 4:30 count time in prison, so I don't eat until 4:30 now.

Stephanie (LPP): There is much more work to be done in the way of cannabis reform. What is the biggest change you’d like to see?

Matthew: Releasing all cannabis prisoners is the first thing. The time people are being given for non-violent cannabis charges, I don't know how anyone on the planet could think it's justifiable. To throw people in prison for a decade for selling a few pounds or a few hundred pounds of marijuana is ridiculous.

Stephanie: I know you also support the rescheduling of cannabis. Why do you lean that way as opposed to descheduling?

Matthew: I don't necessarily see a descheduling. I see the impact that alcohol with no set schedule has on society. But I can't believe, for the love of God. it's a schedule one. I think it should be a schedule three, and maybe if I can look at it through a different set of glasses, it will be completely descheduled. I'm probably one of the few people who see it this way. Now, maybe my motivation for that is I think it would probably help me legally if it was schedule 3 more than it would be if it was descheduled. Do I believe that marijuana is completely harmless? I've wrestled with this statement. I've wrestled with this for years, and I know that when I was abusive with marijuana as a kid, I was so foggy-headed. What's he say in Platoon? That shit kills your will to want to win? I don't know that I agree with that, but I think at least let us study it and find out what it does. We can't even do that. It's ridiculous.

Stephanie (LPP): Thank you so much for taking the time to share a bit of your journeywith us. What's next for you Matthew? What do your short and long-term goals look like?

Matthew: Up to 92 days, my goals were to get a job, stay out of trouble with the halfway house,and not go back behind the fence. Beyond that, I’d like to finish my studies for my degree, expand my career choices, continue going to AA, not using, and spend as much time with my family as possible. I just want to keep my life simple.

Stephanie (LPP): I am so happy you are home and taking the steps to continue thriving in your reentry. Thank you again for sharing some of your journey with us.

Conclusion:

Matthew's story is a powerful testament to the need for cannabis reform and the importance of organizations like the Last Prisoner Project. Through his journey of redemption, he not only seeks to rebuild his life but also advocates for the freedom of others who remain incarcerated for non-violent cannabis offenses. As the cannabis industry continues to evolve, Matthew's experiences serve as a reminder of the importance of compassion, understanding, and criminal justice reform. Together, we can work towards a more equitable and just future for all individuals impacted by cannabis-related convictions.