After Serving 16 Years In Prison for Cannabis, Tom Ranes Needs Your Support Recovering from Medical Neglect

WELCOME HOME TOM

Tom Ranes moved to Anchorage, Alaska from Tensaw, Alabama in 1996 to work in the oilfields. His first job in Alaska was as a welder’s helper. After only six months Tom was promoted to a rig worker at 20 years old. This was unheard of at the time. Clearly Tom was an incredibly talented man who knew how to work with his hands. He was already an excellent mechanic. It was no surprise that within a year Tom bought his own truck with mobile welding capability. In no time, Tom had more work than he could handle alone and was soon hiring employees and renting his own shop space. Tom secured a three-million-dollar loan from The First National Bank of Alaska and the Small Business Administration and Ranes & Shine Welding and Automotive was born! It was comprised of welding, sheet metal, pile driving and oil field services. The local newspaper took notice and touted: “Ranes & Shine Welding Maintains a Climate of Versatility, Innovation and Excellence” and in its business pages stated, “This is the new business in town making its mark in the oil industry.”

It was during this time Tom met a gentleman who would change the course of his life forever. This man hired him to build unique compartment in gas tanks – hidden. Tom being young and from a small country town in Alabama, he was naïve to the reason behind the tanks. But in time he learned what they would be used for. The money was good and much needed for his true goal of building a

successful business. He was pulled into this organization by men who knew how to control others with money, manipulation, fear and violence. Tom soon felt stuck and unable to get out so he compartmentalized what he could and proceeded in life trying to make a success out of his business.

Tom was raising a family which was the most important part of his life. He had two beautiful children; a daughter, Hannah and a son, Emory. Life was good, business was booming and extremely lucrative. Tom had multiple interests and became passionately involved in auto racing. He was the proud owner of a 2003 Ford Mustang Cobra that set track records in Hawaii and at the Alaska Raceway Park as the fastest street-legal car in the quarter mile. It seemed only natural that Ranes & Shine would delve into services for non-fleet vehicles such as installation of roll cages and motors, and anything else that could optimize performance and safety on the race track.

Behind the scenes and unbeknownst to Tom, the federal government had been surveilling the drug ring and it’s two leaders in Alaska for the previous seven years. On April 22, 2006 Tom was indicted along with eighteen co-conspirators and arrested. One of the leaders committed suicide on the day of the raid and the remaining leader was killed. The government then labeled Tom as the “leader, drug kingpin.” While Tom never had a leadership role, this designation of drug kingpin created problems for Tom and his defense. The charges filed were Conspiracy to Import a Controlled Substance (cannabis); International Money Laundering; and Money Laundering.

Tom could not cooperate with the federal government. It was not an option out of fear of retribution from a drug organization that was far reaching. Two leaders now dead, Tom knew he should pay for his part in the drug ring but the feds refused to offer him a deal that matched his involvement. They threatened him with a life sentence, while the co-conspirators were taking and getting 5- and 10- year sentences. Tom was fighting for his life and wanted to go to trial so he could prove the allegations against him were false. In typical fashion, the case dragged slowly and multiple attempts to find legal representation to fight for him in court were futile. Tom was worn down and knew that the odds were 98% against him prevailing at trial against the federal government. They were asking for life in prison so to cut his losses, he pled guilty and accepted a plea deal of 30 years in prison. Tom knew there were only two outcomes; go to prison or be killed. He was in too deep, knew too much and all of the things he cherished in life were in jeopardy. Looking back over this horrific time in his life Tom has acknowledged that his arrest ultimately saved his life. Tom was on his way to serving the next thirty years of his life in a federal correctional institute but he and his family never gave up fighting for his freedom.

Shortly after Tom’s incarceration in the Bureau of Prisons (BOP), he fell from a top bunk in his cell injuring his coccyx and rectal soft tissue causing a thrombosed hemorrhoid. A BOP healthcare worker lanced the hemorrhoid five consecutive days, leading to an infection which caused Tom to lose a significant portion of his large intestine and areas of his abdominal wall. Over the next 16 years, Tom

suffered chronic pain and had to undergo over twenty surgeries. He has had three sections of his large intestine removed due to blockages and has had medical mesh implanted due to an incisional hernia. While mesh is normally absorbed by the body, Tom’s mesh failed repeatedly. Tom had to wear a colostomy bag for two long years. In conjunction with this issue Tom had a severe large herniated disk with free floating fragments pushing on his spine. This was only discovered after he was treated for yet another mesh repair when Tom explained the severe back pain and an MRI of his spine was ordered. With these findings, surgery was recommended for Tom in 2019. Unfortunately, the BOP did not seem interested in helping Tom as he never underwent the surgery. At times Tom was confined to a wheelchair due to his chronic back issues which the BOP refused to either acknowledge or treat. The repeated infections, continued mesh failures, fixing his colon and frequent surgeries have ravaged Tom’s muscle strength and immune system. Tom will require multiple surgeries and procedures to permanently repair the site of the incisional hernias, surgical scars, neglected herniated disc that he received from previous medical errors and substandard care.

In addition to the medical conditions for which Tom was suffering, he received almost nonexistent dental care. He went in with all his teeth but was only seen by dental students. As a result, 70% of Tom’s teeth were extracted. You see the BOP doesn’t believe in preventive care; cavities are not filled, they are pulled.

Life goes on in prison, no excuses. Despite Tom’s severe medical issues, he became an integral part of the work teams. Clearly, Tom was skilled with his hands and had much to offer the BOP in terms of employment and instruction. Tom was assigned many jobs over the years within the BOP. He completed over forty rehabilitative and educational programs as well as holding the position of an instructor for several adult continuing education classes. Jobs included: lead welder building the military M-RAP and armored hummers that were being used in the Iraq war. He was teaching other inmates welding and fabrication in preparation for their post-prison employment. Tom received several well- deserved commendations from his employers shown as follows:

- Working for the Facilities Department at FCI LaTuna, his supervisor Mr. Le wrote the following:

“Ranes was always first to work and always last to leave and he has an exceptional work ethic. He completed his work with a journeyman-level product and a can-do attitude.” He also noted, “with Mr. Ranes’ help I was able to complete many projects that would have required a lot more time to complete. Mr. Ranes was also an outstanding role model to the other inmates. Mr. Ranes stayed clear of disciplinary issues that would affect the other inmates.”

- Another supervisor at FMC Ft. Worth wrote of Tom:

“I can truly say in 17 years of working in this trade I have seen few who can accomplish his quality of work. We are often limited in supplies, tools, and equipment. Tom Ranes improvises and completes any task assigned. He is also known for his initiative. He can often spot problems and finds solutions without direction. Initiative is not a common quality within this institution.”

In conjunction with his work life, Tom also participated in multiple arts and crafts courses that kept him close with his son and daughter. He would create art, ceramics and leather goods to send to his children.

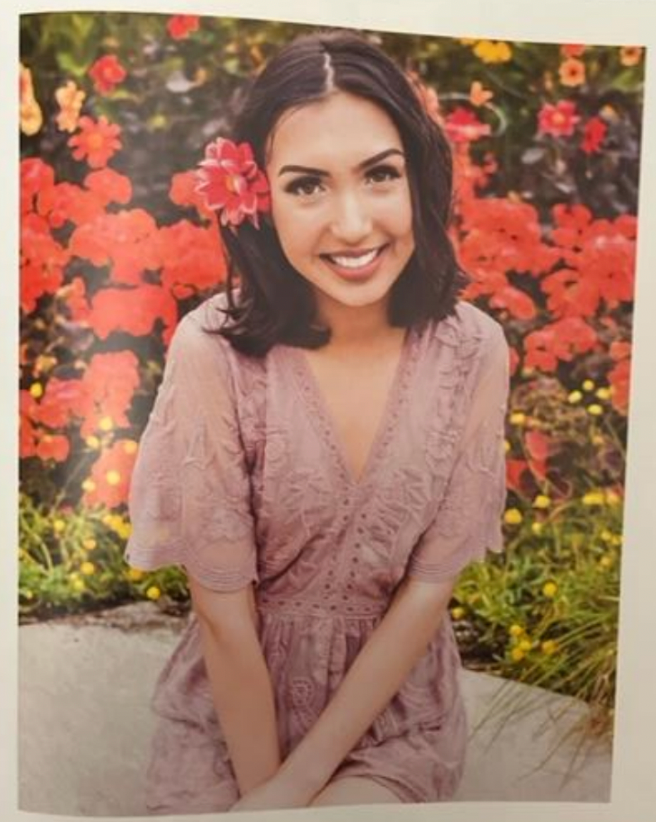

It is no surprise that Tom took his artistic pursuits as seriously as everything else he did. He maximized his phone calls with Hannah and Emory to keep their relationship strong. Hannah was just six years old when Tom left for prison and Emory was just a toddler. Against all odds and because of his focus and determination, Tom’s bond with his children only grew while he was incarcerated. Sadly, Tom received the devastating news that his beloved, beautiful daughter, Hannah unexpectedly passed away on May 16, 2022 at the age of 22 years old. One cannot fathom the utter despair a parent must feel when suffering this kind of loss. Compound that with being in prison alone when your reason for living has been suddenly, drastically – changed. It was during this time of intense mourning that Tom, recognizing he qualified for The Cares Act, filed for a compassionate release. He knew he must get home to see his son, Emory. By this time Emory, a gifted student, who finished high school in two years was currently attending The University of Florida. He is studying pre-medicine with plans to specialize in orthopedics. To say Tom is proud, is an understatement.

A Motion for Compassionate Release was filed in July 2022. This motion sought a reduction in sentence which effectively would allow Tom to serve the balance of his sentence at home subject to 2 years home confinement and after that 6 years’ probation. This court granted this motion and Tom was released from prison on December 15, 2022.

Tom considers himself fortunate to have a supportive family located in Alabama where he will be subject to home confinement for the remainder of his sentence. Tom is currently living and working with his brother at his landscaping business which specializes in building retaining walls, docks and boathouses and installing paver driveways. Tom plans to become a partner in the business and add welding to the list of services offered and hopes to buy equipment such as pile drivers to work more efficiently. His brother is able to work around Tom’s multiple physician appointments that are required to get his health back on track. His sisters have also helped Tom with his transition home by tutoring him to become computer proficient. Sadly, Tom and his family are also dealing with aging parents. His father lives in a VA facility and is legally blind. His mother needs around the clock care.

Tom is starting his life over with nothing financially. His most pressing priority is getting proper medical care. The substandard care Tom received while serving his sentence in addition to the pain limitations under which he is currently living is simply put – unconscionable. The first thing Tom acquired upon his release was a medical plan. Unfortunately, it came with a $7,200 deductible. In addition, the BOP which requires home monitoring, charges him $112.00 per month for the ankle monitor they require him to wear. He hopes that some relief could be provided by the community that is building stock portfolios from the very commodity for which his is still serving a thirty-year sentence.

Tom Ranes, is and always had been, an optimist. In the midst of the needless suffering he has endured, inflicted upon him by the substandard care provided by the BOP, he has steadfastly maintained his belief that most people are good, and that his unfortunate collision with the federal government is part of the hand that life has dealt him. It is obvious from Tom’s story that he not only maintained his positive outlook, but that he used the time that was taken away from him, to develop himself into a better person with even more talents and skills, despite the limitations of incarceration. At the same time, he shared his hard-won knowledge and enduring positivity to help others better their lives. There are no pity parties here. Tom looks forward to reestablishing his ties to both his community and his family, particularly his son, Emory. His first order of business is attending to his health. Tom has proven that his spirt can’t be broken. He did not let the years of his incarceration prevent him from being a light in this world. Being back in the community and becoming as healthy as possible, Tom’s light will continue to shine for so many more people that he can now reach.

PLEASE SEE THE BELOW GO FUND ME FOR TOM. YOUR HELP IS APPRECIATED:

This article was written by one of Tom's advocates, Mitzi Wall (mitzifwall@gmail.com)