Finding Freedom and Purpose: Deshaun Durham's Story

The holidays are a time for joy, family, and reflection. For DeShaun Durham, this past New Year’s Eve marked a profound moment of gratitude and rediscovery—the first time in three years he could celebrate surrounded by loved ones. His journey back to freedom is not just a personal triumph but a testament to the resilience of the human spirit and the urgent need for reform in how we treat cannabis-related offenses.

DeShaun’s story begins in Manhattan, Kansas—the "Little Apple"—where he grew up. Like many teenagers, he struggled with depression and found solace in cannabis. By 21, however, his involvement with the plant led to a life-altering experience: a raid on his home that ended with 15 armed officers pointing guns at him. The crime? Possession of 2.4 pounds of cannabis in a state where it remains illegal. The punishment? An excessive sentence of 92 months in prison.

The disparity in how cannabis offenses are treated across the United States is glaring. In states like Colorado and California, cannabis is a thriving legal industry. Yet in Kansas, DeShaun’s life was derailed for possessing what many now buy legally. “The prosecutor told me at one of my preliminary hearings that I got caught with cannabis, so that meant I deserved to go to prison,” DeShaun recalls. He’d hoped for probation. Instead, he faced the loss of his twenties and a bleak future.

DeShaun’s initial months in prison were harrowing. Transferred to a Super Max facility, he endured inhumane conditions: unbearable heat, 10-by-10 cells, and a mere 15 minutes outside each day. He feared that this might be his reality for the next eight years. Yet, amid the despair, hope flickered.

The turning point came when Deshaun decided to apply for clemency. Despite the skepticism of fellow inmates who had seen countless applications ignored, DeShaun pressed on. His determination to reclaim his life was unwavering, even as he anxiously watched Kansas’ gubernatorial election, knowing that a change in leadership could seal his fate. When Governor Laura Kelly, a Democrat, was re-elected, DeShaun’s hope grew stronger.

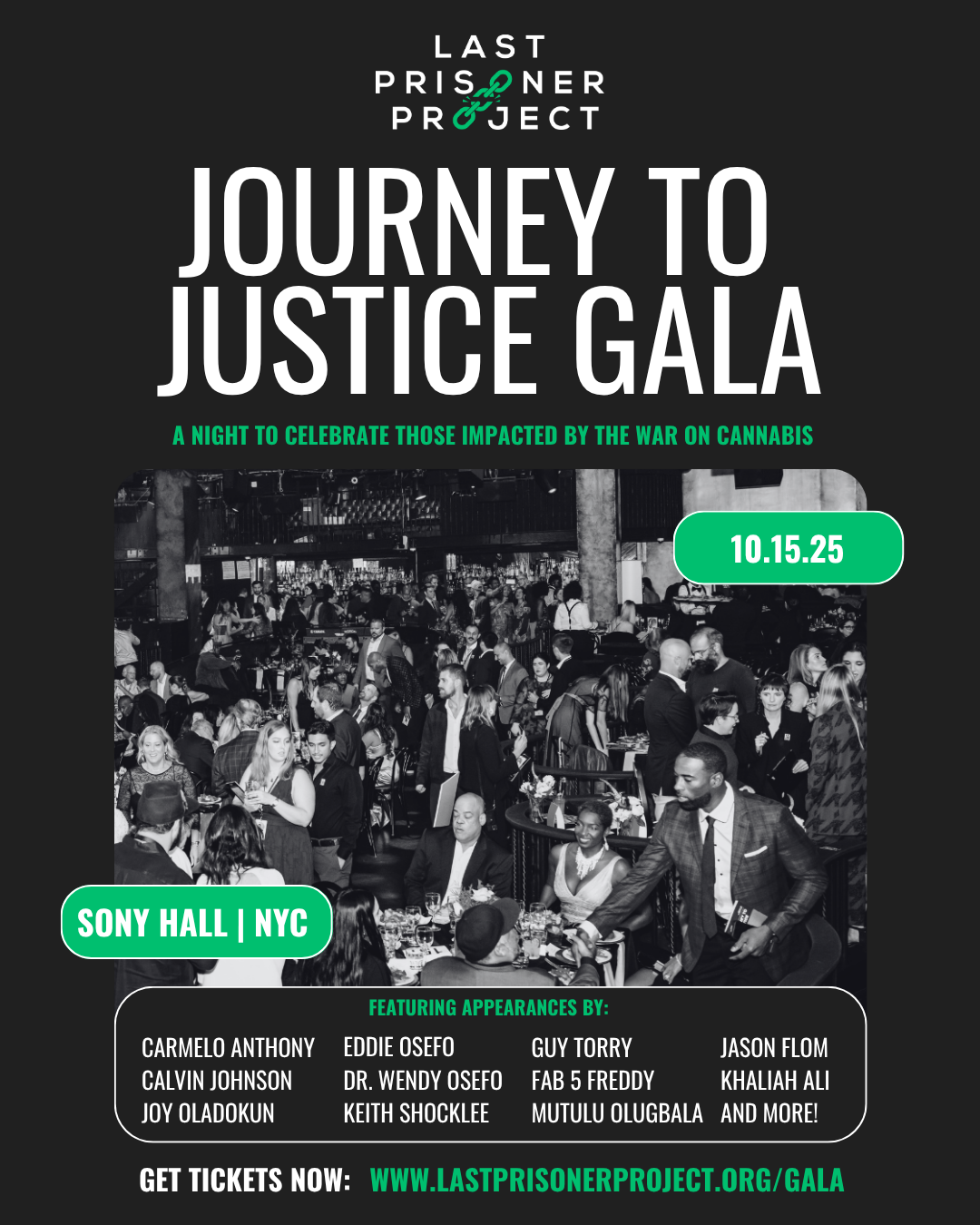

A key figure in DeShaun’s journey was Donte West, a fellow advocate who understood the struggles of incarceration. Through connections and the support of an organization; Last Prisoner Project, DeShaun’s case gained traction. Donte’s commitment to helping others resonated deeply with DeShaun’s situation, and together, they navigated the labyrinth of legal appeals and advocacy.

The moment DeShaun learned his sentence had been commuted is one he will never forget. “It felt like my spirit had left my body,” he says, recalling the shock and disbelief. For the prison attorney who delivered the news, it was a rare and remarkable moment in his 30-year career.

For DeShaun, it was the beginning of a second chance.

Now, as a free man, DeShaun reflects on the broken system that took years of his life. His story is a stark reminder of the urgent need to address cannabis-related incarceration, especially as societal attitudes toward the plant continue to shift. Deshaun’s resolve to use his experience to help others is inspiring. He’s determined to make his voice heard, to ensure that others don’t face the same fate he did.

DeShaun’s story is not just his own. It’s the story of countless others who remain behind bars for offenses tied to a plant that is increasingly embraced across the country. It’s a call to action for policymakers, advocates, and communities to push for reform. Most importantly, it’s a reminder that even in the darkest moments, hope and perseverance can light the way to freedom.

Last Prisoner Project: First question...how were your holidays?

Deshaun Durham: They were good. I'm glad I got to do something on New Year's Eve. Being around my family for the first time in 3 years was nice. It was a great feeling to be able to enjoy that again.

Last Prisoner Project: What did bringing in a New Year feel like? It's really New Year, new you from what you did last year to this past year. Since you've been out, you've even gone to a couple of Kansas City Chiefs games, how has that felt for you?

Deshaun Durham: It was a good feeling. I'm glad I could spend my new year trying to help others and make their voice heard. Holidays had been taken away for so long that they hit differently. It was hard to be locked up and not be around your family while being in a negative environment when the holidays are supposed to be a happy time.

Last Prisoner Project: What have your Christmases, Thanksgivings, and New Year's been like for the past 3 years?

Deshaun Durham: I tried not to think about it, taking them as just another day. You don't want to think about moments like that when you're in prison because it makes the time harder.

Last Prisoner Project: Can you talk a bit about these past few years and how you found yourself away from your family, where you've been for the past 3 years, and how you got there?

Deshaun Durham: I was in a Hutchison Correctional Facility in Hutchison, Kansas. I had gotten caught with 2.4 pounds of cannabis in Manhattan, Kansas. My home was raided, my door was kicked down, and there were about 15 police officers, all with their guns pointed at me... just to find some cannabis. I found it excessive that I had guns pointed at me for a plant that's legal in so many states. I was on bond for 2 years while I worked a job and stayed out of trouble, but they still felt the need to sentence me to 92 months in prison. The prosecutor told me at one of my preliminary hearings that I got caught with cannabis, so that meant I deserved to go to prison.

Last Prisoner Project: What's your background? Where did you grow up?

Deshaun Durham: I grew up in Manhattan, Kansas, my whole life. Some people call it the Little Apple.

Last Prisoner Project: That's funny. When did you become involved with the plant?

Deshaun Durham: At a very young age, I was probably in the 7th grade. I know I was a little young, but I was a kid that always got bullied. I struggled with a lot of depression, so I picked it up fairly early on in life, but it helped me through a lot of tough times, growing up. I'm just glad I was able to find a way to help me keep going in life.

Last Prisoner Project: Is that why you decided to help bring that to others who may be struggling?

Deshaun Durham: That was in 2018. I was going through another tough time because, having a lot of family issues, I had no money and nowhere to go. In my mind, I was thinking, "Oh, it's just weed, everyone loves weed. I'm not going to get in that much trouble for it. I'll probably get probation. I know it's illegal in my state, but I won't get in that much trouble." I'd never been in that kind of trouble before in my life. Reality hit me when they started tossing out the 92 to 144 months, and that's when I began to see I was mistaken about how harsh they would be towards me.

Last Prisoner Project: Do you attribute that to being ignorant of the process or naive to the seriousness of where the system was with cannabis?

Deshaun Durham: Both. I didn't know what could happen, and I didn't think cannabis was that serious.

Last Prisoner Project: You were very young when this all happened. At what age did you get incarcerated?

Deshaun Durham: I was 21.

Last Prisoner Project: 21. So as a young man facing these 8, maybe more, years in prison that they were throwing out at you. How did you process the sentence you were given when you knew that that was your sentence?

Deshaun Durham: Yeah, it was a lot of, you know, just like thinking that like, Oh, I lost my whole twenties, and you know I didn't know what prison was like, you know, I was kind of like, oh, I wonder what's gonna happen? I was just this young kid who's never been in trouble in his life. So you see, all the TV shows and everything like, Oh, people in prison, you know, they're going to do bad things, or this is going to happen, and that's going to happen, and was just ignorant to the situation. I thought prison was a bad place and nothing good would come out of it. I was thinking that my life was over essentially for almost 10 years. I thought I would get out of prison with nothing and be almost 30, and I wouldn't have any friends because they would have all moved on, forgetting about me.

Last Prisoner Project:

At what point while you were incarcerated did it set in for you when you were sitting there and you thought that this was your fate? Or maybe you didn't. Maybe you were always like, no, I'm going to get out of this.

Deshaun Durham: Reality kicked in when I was being processed in Super Max, where I was for four months. It was a rough experience. It was during the summer, there was no A/C, and I was stuck in a 10 by 10 cell. I just remember it being so hot. I had no bed sheets or anything on my bed, and I was thinking, man, I hope this whole 8 years isn't like this! People would try to open the windows to get some relief from a breeze, but then the officers would come in with the maintenance people and cut all the knobs off the windows so people couldn't open the windows. We only got 15 min out every day, so I couldn't talk to my family during that time. I had hope that I could get out early because everyone, even the officers, when I told them how much time I got for what I did, would say, "Oh, you need to appeal. That doesn't even make any sense!" I kept hoping that if other people agreed that it wasn't fair, maybe people higher up would agree with it also.

Last Prisoner Project:

You spoke about your family. Tell me about your family and how they were affected by your incarceration.

Deshaun Durham: I live with my mom, my little brother, my sister, and my mom's husband right now. My dad lives in New Hampshire, and a lot of relatives from my dad's family live in Massachusetts. I have 3 sisters and a brother there. My sisters are twins, and one of them had a baby while I was locked up, so I'm an uncle now. I haven't even had the chance to meet my new niece yet.

Last Prisoner Project:

Being close to your Mom, in what ways did you see your incarceration affect her?

Deshaun Durham:

It definitely hurt her. She was really the only person I could talk to when I was having a bad day or when things weren't going right. She didn't want to hear me down and depressed every day.

Last Prisoner Project: Did you ever feel the need to hide how down you really were, or did you portray to her that you were doing better than you were, for her benefit?

Deshaun Durham: Sometimes. There were times when I didn't want to talk to anyone because I didn't want to burden them with my problems. I just wanted people to enjoy life out there and I was just going to accept the reality for what it was.

Last Prisoner Project: You started to feel like there was help for you out there. How did you start your journey to reunite with your family and continue with your life?

Deshaun Durham: Between the heat and the poor conditions, I knew I didn't want this to be my foreseeable future. I heard that I could turn in a clemency application. I knew so many people who turned in clemency applications but got nothing. They would say, "Oh, yeah, good luck with that, I've been waiting on my clemency for, like ten years and three governors", but I thought it was worth a try. I filed and also wrote a nice 4-page letter to the governor and told myself, "I turned it in, now I just have to wait." I knew that a Democratic Governor would probably be my best shot at any action. It was an election year for Kansas Governor. I stayed up all night looking through the window of my cell at the TV, watching the election, sweating, and hoping that Laura Kelly won because I knew if she didn't win, my chances might not be as good. Thankfully, she won. It was a relief. I've never been so in tune with an election like that until it directly affected me.

Last Prisoner Project: Donte West, at what point did he enter your world?

Deshaun Durham:

I was in the same place where he served time. When I got sent to Hutchinson, I met another inmate, Antonio Wyatt, and I told him about my case. He told me that he had a similar case, and he said, "Well, I know these people that could help you. I was locked up with my Guy, Donte when I was in Lansing, and we made a pact that whoever got out first, we'll try to get the other out. I could give him your information and have him work on your case because I hate seeing you in the same situation as me, and you're a lot younger than me." If it wasn't for Antonio, I would have never found Last Prisoner Project or Donte, and it probably wouldn't have worked out the same way.

Last Prisoner Project: Donte took a huge interest in your case. He's passionate about all that he does as an advocate, but I think something in you, he saw in himself, with your age and different things that you've gone through in the past, it seemed to resonate with him, and he took it to heart and pushed it to the point where you were up for clemency. When you learned about your clemency being granted and that you were going to be released, what was your first thought?

Deshaun Durham: I remember the exact moment that I found out because it was a bad day. I was mad because I lost a card game. I hopped on the phone to call my mom, but she told me to call her back in 10 minutes, so I decided to check my messages on my tablet and I saw that I had a message from Mary Bailey, and it was in all caps, GOVERNOR KELLY COMMUTED YOUR SENTENCE! It felt like my spirit had left my body, and I was looking down at myself, I didn't think it was real.

Last Prisoner Project: Being told that this nightmare is over must have made the day better.

Deshaun Durham: I felt like I was dreaming. The attorney for the prison walked up to me with a letter in his hand and said, "I had to hand-deliver this letter to you, and this doesn't happen often. This is the first time I've seen this happen, and I've been at Hutchinson for 30 years!" He told me to make the best of my opportunity and don't get in trouble again. It was like everyone in the prison, you know, was happy for me because everyone was congratulating me, even the guards were congratulating me. I think it was the first person in Hutch who got that type of relief almost four and a half years early.

Last Prisoner Project: It should happen much more. That's why not only was your family rooting for you, but you saw other prisoners and even the officers wanting justice for you. Many people were out here so excited when the announcement was made about your release. When I got home, I felt anxious, how are you feeling? Do you think about how blessed you are by being home so soon?

Deshaun Durham: I'm still taking it in and just trying to enjoy life. I'm working at a Chinese restaurant and trying to save as much money as I can. I'm still on parole, but when I get off parole, I think I'm going to move to Kansas City, Missouri, and turn this experience into something productive. I want to find my spot in the legal cannabis industry. I have been researching steps I could take to find what fits for me. I'm passionate about cannabis, and since I lost 3 years of my life in prison because of the criminalization of the plant, I think it's only right that something good comes of it.

Last Prisoner Project: At any point through this process, was there a sense of guilt that you were getting out and leaving people behind? And is that why you're now so passionate about giving that hand back to people who are still incarcerated?

Deshaun Durham: I met a lot of good people there. One guy's been in prison for 11 years for like 90 pounds, and he still has two more years to go. I'm just tired of the injustice. It's ruining people's lives and taking them away from their families. I just want to help as many people as I can with the opportunities I've been given.

Last Prisoner Project: We at LPP are grateful that you have been so generous with sharing your story. People must understand the impact of what being incarcerated for a cannabis-related offense is really like, and you're a perfect spokesperson for it. As we move forward, we are now advocating to a different administration. As we continue to fight, if you could snap your fingers, what would you like to see change with cannabis reform?

Deshaun Durham:

I think it should be legalized federally and regulated like alcohol and tobacco. Of course, anyone who's been in prison or is still in prison for cannabis should be free, and the barriers of entry to the legalized industry should be lifted for anyone who's ever been to prison for cannabis. I look forward to getting to the point where no one has to worry about getting a harsh punishment for a plant anymore.

Last Prisoner Project: I certainly hope that we get to hear your voice this year for 4/20 Day of Unity. Last year for 4/20, it was amazing to get so many organizations together that all have similar goals toward cannabis reform and and hear the voices of people like Donte West and Kyle Page.

Deshaun Durham: I'll be there.

Last Prisoner Project: When you were incarcerated, the industry was already up and flourishing so knew what the legal industry looked like right?

Deshaun Durham: Yes. The hardest days were on 4/20 when I'd watch the news, they'd have a Stoner Movie Marathon, or they'd show all the 4/20 parades. I was serving 8 years for something that everyone was enjoying on that very day.

Last Prisoner Project: You have 24-36 months of parole. Are you feeling any pressure from that? Are you nervous about completing the parole, or is it already set in your head that you are going do this with no problem because you know the alternative, the other side of things?

Deshaun Durham: I'm not worried. I haven't smoked for so long that I can wait to smoke for two more years. I'm not going to have any problems because I mostly just work, go home and do my research. I know that I can be more of a help to you guys when I'm off parole, and I can travel and do other things. There is a little bit of anxiety because there's so much that I want to accomplish. I got out, and I want to help other people in my situation. I'm ready to start this first full year out in a positive way and see what it brings. Hopefully, there will be some doors opened for me to some good opportunities where I can better myself and my future.

Last Prisoner Project:

I know that there are a lot of people in your corner. Many LPP partners believe in second-chance hiring and will surely welcome you into the legal space when you're ready. I think it's very cool that Donte is giving that hand, and he gave that hand to Kyle Kyle Page, and Kyle Page is giving that hand to other people. And now you are an extension of that.

Last Prisoner Project: So, you know, let's knock on wood and hope that the current administration releases some people. What would you say to them?

Deshaun Durham: Yes, most definitely. I would just like to say it's a very senseless and barbaric war, and the people deserve to be free. For something that has zero confirmed overdoses, and has very little, if any, negative effects on society. I just feel like everyone deserves to be free.

Last Prisoner Project: Thank you so much for sharing some of your journey with us and speaking out for those who can't speak for themselves.