4th of July Freedom Paradox: The Unfair Reality for Our Longest Serving Constituents

As U.S. Celebrates 247 Years of Independence, Our Longest Serving Constituents Have Collectively Been in Prison For the Just Over the Same Time

At the heart of the Last Prisoner Project (LPP) lies a deeply held belief: no one should be imprisoned for offenses that are now legal. Herein lies the paradox of celebrating Independence Day in America when the War on Drugs still rears its ugly head. To right the wrongs of America’s War on Drugs, it is important to advocate for those unjustly incarcerated due to outdated marijuana laws.

Each of the men below are casualties of the current war on marijuana in the United States. They have spent years behind bars for non-violent marijuana offenses. And on July 4th, Independence Day, they still remain behind bars. Their stories highlight the urgent need for reform. As we work to free tens of thousands of individuals still imprisoned and push for systemic change, we want to share their stories on this Independence Day.

Jose Elias Sepulveda

- Sentence: Life

- Amount of Time Served: 25 years

- Jose Elias Sepulveda has spent over 25 years behind bars. Sepulveda has already served two decades of his sentence. Despite his life sentence, Jose remains hopeful and resilient, and looks to contribute positively and productively to society if ever released.

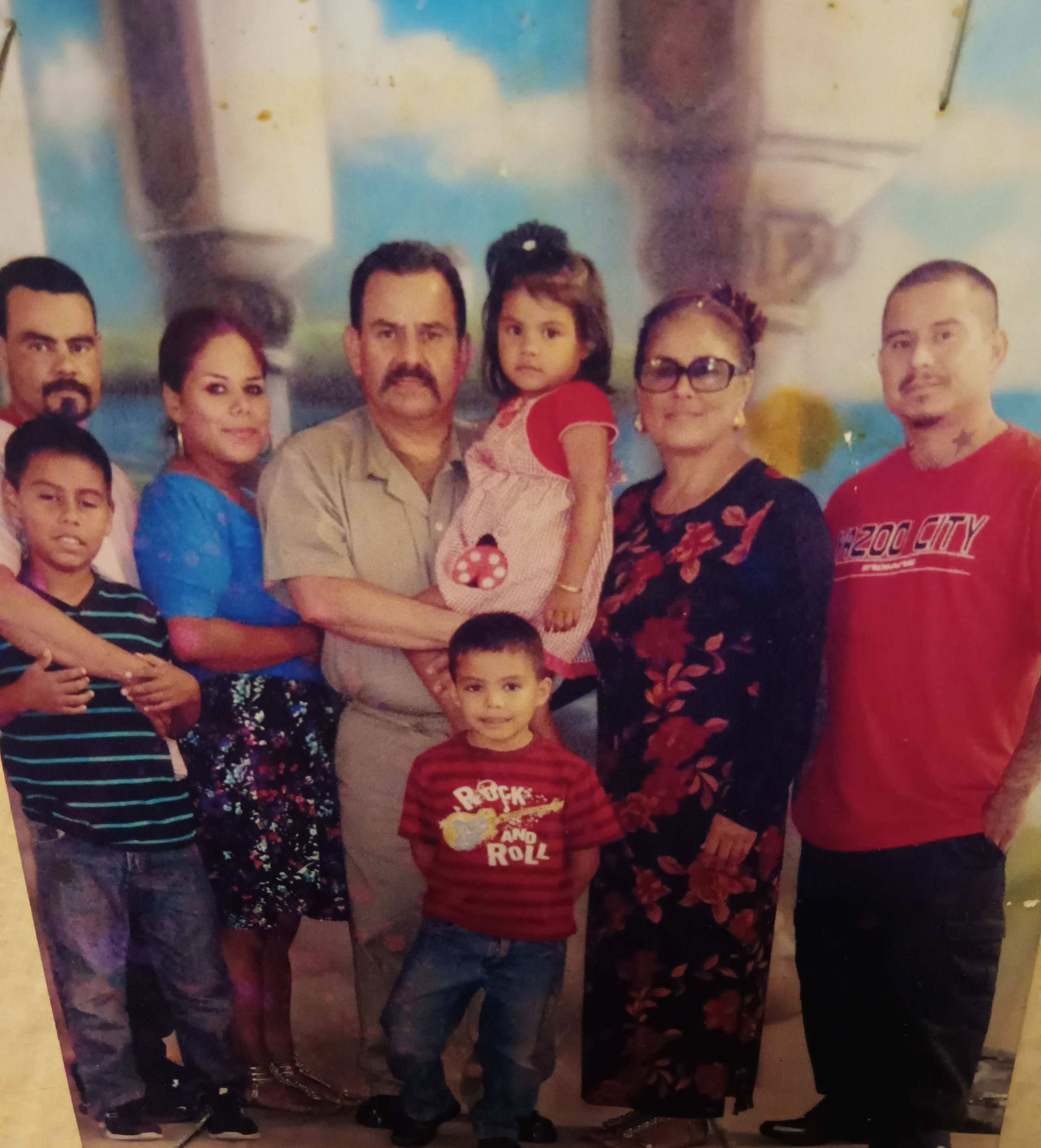

Pedro Hernandez

- Sentence: 240 months plus 3 years supervised release

- Amount of Time Served: 25 years

- Pedro Hernandez is now 66-years-old, and has served approximately one-third of his sentence. Since his imprisonment, there has been no record of any further criminal activity. If we are unsuccessful in our advocacy efforts, Pedro may not be eligible for parole until October 2084. We won't stop fighting until he is fully free.

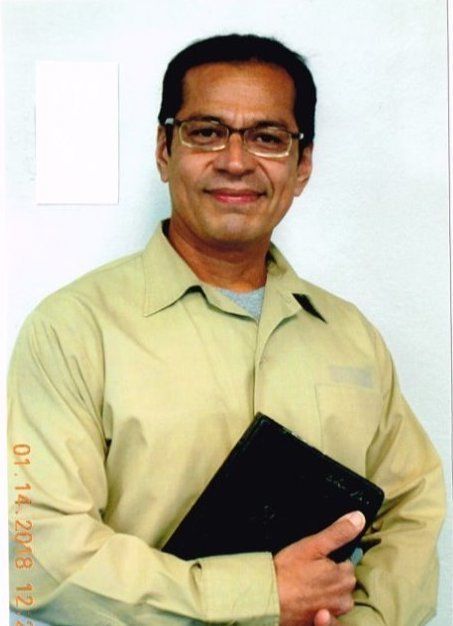

Edwin W. Rubis

- Sentence: 480 months plus 5 years supervised release and a $25,000 fine

- Amount of time served: 26 years

- Edwin W. Rubis, serving a 40-year sentence, has faced significant challenges yet continues to persevere. After overcoming his struggle with addiction, Edwin has taken numerous steps to better himself while incarcerated. He graduated from college with a degree in Religious Education and serves as a mentor to others. He is also working as a G.E.D. and E.S.L. tutor in the education department. With the support of LPP's scholarship program, Edwin recently received his Master's degree in counseling and now hopes to pursue a Doctorate.

Jose Antonio Trejo-Pasaran

- Sentence: 420 months plus 5 years supervised release

- Amount of Time Served: 22 years

- Jose Antonio Trejo-Pasaran's story reflects the harsh reality of lengthy sentences given to those involved in organized crime. His resilience is a testament to the human spirit’s ability to endure and hope for change. Without our advocacy efforts, Jose will most likely be in prison longer and won’t be up for parole until September 2031.

Tennyson W. Harris

- Sentence: 324 months plus 10 years supervised release

- Amount of Time Served: 21 years

- Tennyson W. Harris, facing nearly three decades in prison, continues to demonstrate remarkable strength. In comparison to Tennyson’s Co-Defendants involved in his case, Harris received the longest sentence. Meanwhile, all of the co-defendants are no longer in custody.

Jose Alfredo Jimenez

- Sentence: 292 months plus 5 years supervised release

- Amount of Time Served: 20 years

- Jose Alfredo Jimenez's journey is a stark reminder that all lives can be affected by stringent drug laws and that some of our strongest allies in the movement can be those that can change the minds of our opponents. Jose is now 66 years old with Parkinson’s disease, and has already been incarcerated for over 19 years.

Leonel Francisco Villasenor

- Sentence: 360 months plus 4 years conditional release

- Amount of Time Served: 20 years

- Leonel Francisco Villasenor is trying to make a change while imprisoned. This is evidenced by those who work with Leonel on a day-to-day basis, and give him the highest marks and compliments. Leonel needs our advocacy efforts or he could be imprisoned for longer, with an opportunity for parole in May 2028.

Gabriel David Gomez

- Sentence: 360 months plus 5 years supervised release and $5,400 special assessment

- Amount of Time Served: 19 years

- After being sentenced in 2005, Gabriel Gomez went on to complete his GED that same year. Since then, he has completed 40+ educational courses, from Interview Skills to Advanced Accounting. Gabriel hopes to be released to his family in New Mexico before his 60th birthday.

Charles Macheleani Beamon

- Sentence: 999 years, 99 months, 99 days

- Amount of Time Served: 19 years

- Charles Macheleani Beamon’s is a prime example of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. In a letter to LPP, Charles details how a friend’s marijuana somehow got blamed on him. Charles' interaction with officers then led to his arrest and now all he wishes for is to be released from the violence that occurs inside prison walls on a daily basis.

Harold Klump

- Sentence: 360 months plus 10 years supervised release

- Amount of Time Served: 18 years

- Harold Klump has spent his entire adult life behind bars. Despite facing a 30-year sentence, Harold’s spirit remains unbroken. Harold’s imprisonment serves as a poignant reminder of the marijuana law paradox we confront on Independence Day.

Ismael Lira

- Sentence: Life

- Amount of Time Served: 18 years

- Ismael Lira has been serving a life sentence since 2006. His life imprisonment sentence makes no sense for a man with a nonviolent past. Ismael shared, “To those who [support] the Last Prisoner Project's efforts, I would like to say thank you. Thank you for your support and the assistance you've provided to right the wrongs of egregious sentencing for cannabis.“I was [sentenced] to life in prison for possession with intent to distribute cannabis. There were no eyewitnesses, no physical seizure of the supposed 100 kilograms (which turned into 1,000 kilograms for not pleading guilty which then carried a life sentence). All based on evidence from a DEA agent who was recently convicted on multiple counts of falsifying evidence and records. “For those who are in my circumstances...don't lose hope. For those who are unaware of what transpires in our legal system, I hope this gives you pause. And for those who are trying to help those in need — I thank you all; without your support, nothing will change."

Hector McGurk

- Sentence: Life

- Amount of Time Served: 17 years

- Hector 'Reuben' McGurk was vilified in the media as a “drug kingpin,” and was sentenced to life after a hung jury failed to find him guilty the first time. Federal prosecutors tried him a second time and he was convicted of this marijuana offense and was given a life sentence. He is currently 62 years old and has been incarcerated for 15 years. He is one of the three constituents, amongst many others not featured, serving life in prison for a non-violent offense. Ruben will die in federal prison for a nonviolent marijuana offense if he does not receive a commutation.

Donald Burns

- Sentence: 30 months plus 2 years supervised release

- Amount of Time Served: 2 years

- Even though Donald Burns' has a shorter sentence than others on this list, his incarceration exemplifies what he calls a “corrupt system.” Donald penned his thoughts about the system in a letter to LPP. He wrote: “Happy Fourth of July! And hopefully this shall be the final year that the insane and corrupt US Government shall be incarcerating US Citizens for a product which is sold only a few miles away from where I am incarcerated as well as only a couple of miles from my home. The only other equitable solution would be for the Governors and Legislation of all States which current[ly] sell marijuana legally should be arrested and imprisoned for selling an illegal product according to the US Legal Codes.”

These stories remind us why we do what we do and why we must continue to fight for justice. And why we need your help. This Independence Day, let's fight for these individuals and many others who are unfairly imprisoned by continuing to advocate for their freedom. Join us in our mission to ensure that no one remains a prisoner of outdated and unjust marijuana laws. Let's celebrate the true spirit of freedom and justice this 4th of July by taking action at www.lastprisonerproject.org/takeaction.