LPP Asks Hawai'i to Prioritize Retroactive Relief for Those Criminalized for Cannabis If Seeking to Legalize

Testimony Statement from Frank Stiefel

Senior Policy Associate

Last Prisoner Project

RE: Senate Bill 3335, Prioritizing Retroactive Relief for Those Criminalized for Cannabis If Seeking to Legalize

February 9, 2024

Dear Members of the Committees on Judiciary and Health and Human Services,

When a state legalizes adult-use cannabis, it is acknowledging that public interest has turned against the continued criminalization of cannabis. However, simply repealing the prohibition of cannabis is insufficient: millions of individuals across the U.S. still bear the lifelong burden of having a cannabis record, and tens of thousands are actively serving sentences for cannabis-related convictions. Thankfully, the inclusion of criminal justice policies has become commonplace for states that have sought to legalize adult-use cannabis. Since 2018, 13 of the 14 states that have legalized cannabis have included record clearance policies, and since 2021, they have all been state-initiated. While resentencing policies have been slower to take hold, they are also growing in importance and have been included in more than half of the legalization bills since 2020.

The Last Prisoner Project (LPP) has worked diligently over the past two years to present evidence-based policies that will ensure that retroactive relief is provided for those who have been criminalized during the War on Drugs. In 2022, LPP presented

recommendations to Hawaii’s Dual Use of Cannabis Task Force for the creation of state-initiated record clearance and resentencing processes for those who continue to suffer from criminal convictions and sentences as a result of prohibition. LPP’s recommendations were endorsed by the Task Force and were codified in SB 375, SB 669 and HB 237 during the 2023 legislative session. Additionally, LPP was named in

Concurrent Resolution No. 51/House Resolution No. 53, which urged Governor Green to initiate a clemency program for individuals who are still under supervision for a cannabis conviction.

As technical assistance providers, we have read, advised, and informed expungement and sentence modification statutes across the country. We understand that proposing any state-initiated process represents no small undertaking and requires a reasonable amount of time to develop the necessary technological infrastructure and business processes in order to ensure a system is implemented with fidelity. Based on our conversations with various agencies in Hawai’i, we have developed and submitted for the consideration of this committee, proposed legislative language that provides retroactive relief for those who have been criminalized during prohibition. Importantly, our proposal would not run afoul of the redlines given by the Attorney General in the

Report Regarding the Final Draft Bill Entitled “Relating to Cannabis.”

If SB 3335 can contemplate the creation of 17 new law enforcement positions, and an entirely new market and regulatory structure, then surely Hawai’i can also dedicate the necessary resources to addressing and repairing the harm caused by decades of cannabis prohibition.

We thank you for your consideration of this urgent matter.

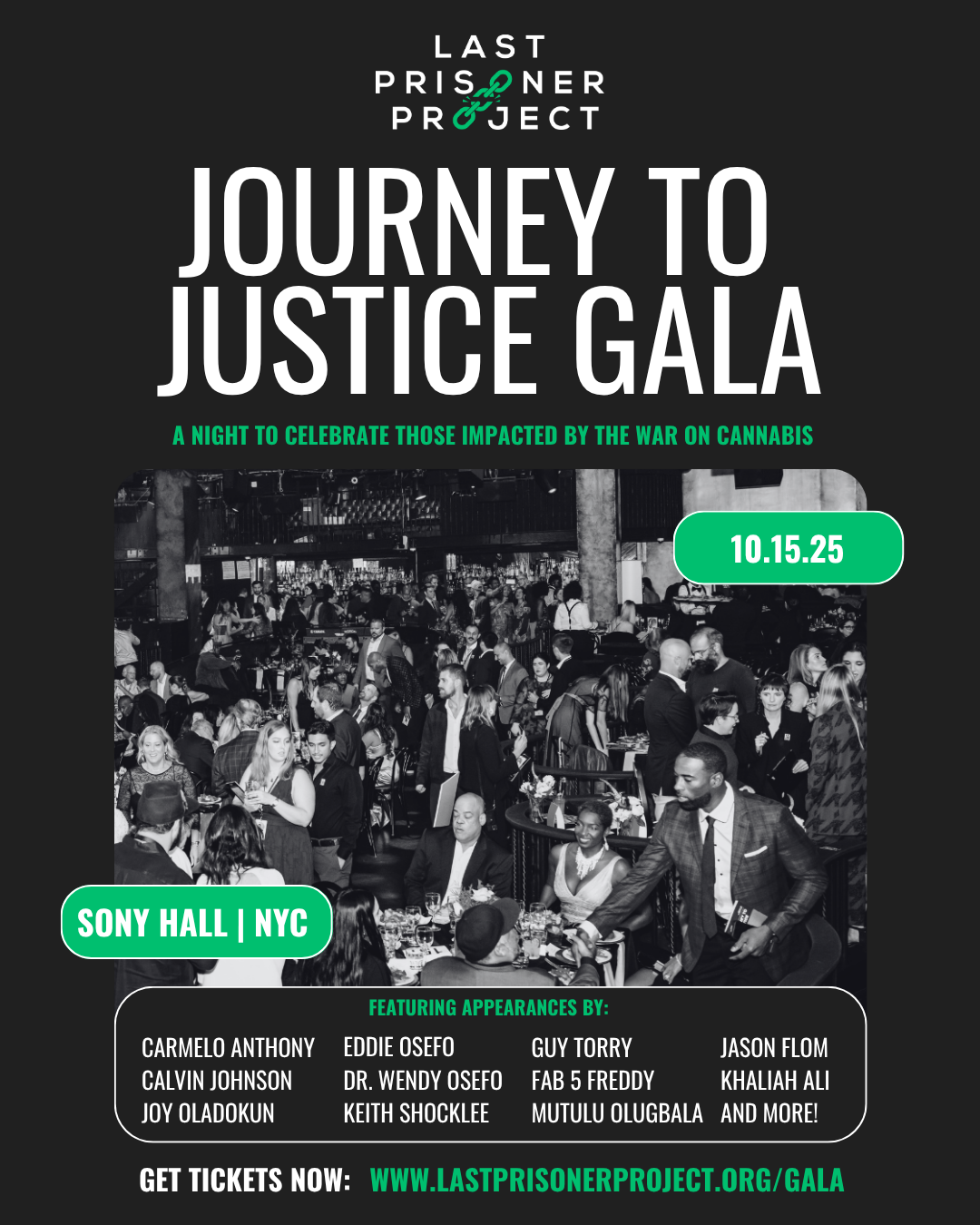

About Last Prisoner Project

The Last Prisoner Project, 501(c)(3), is a national nonpartisan, nonprofit organization focused on the intersection of cannabis and criminal justice reform. Through policy campaigns, direct intervention, and advocacy, LPP’s team of policy experts works to redress the past and continuing harms of unjust cannabis laws. We are committed to offering our technical expertise to ensure a successful and justice-informed pathway to cannabis legalization in Hawai'i.