Blossoming Beyond Boundaries: A Cannabis Felon’s Journey to a Brighter Future.

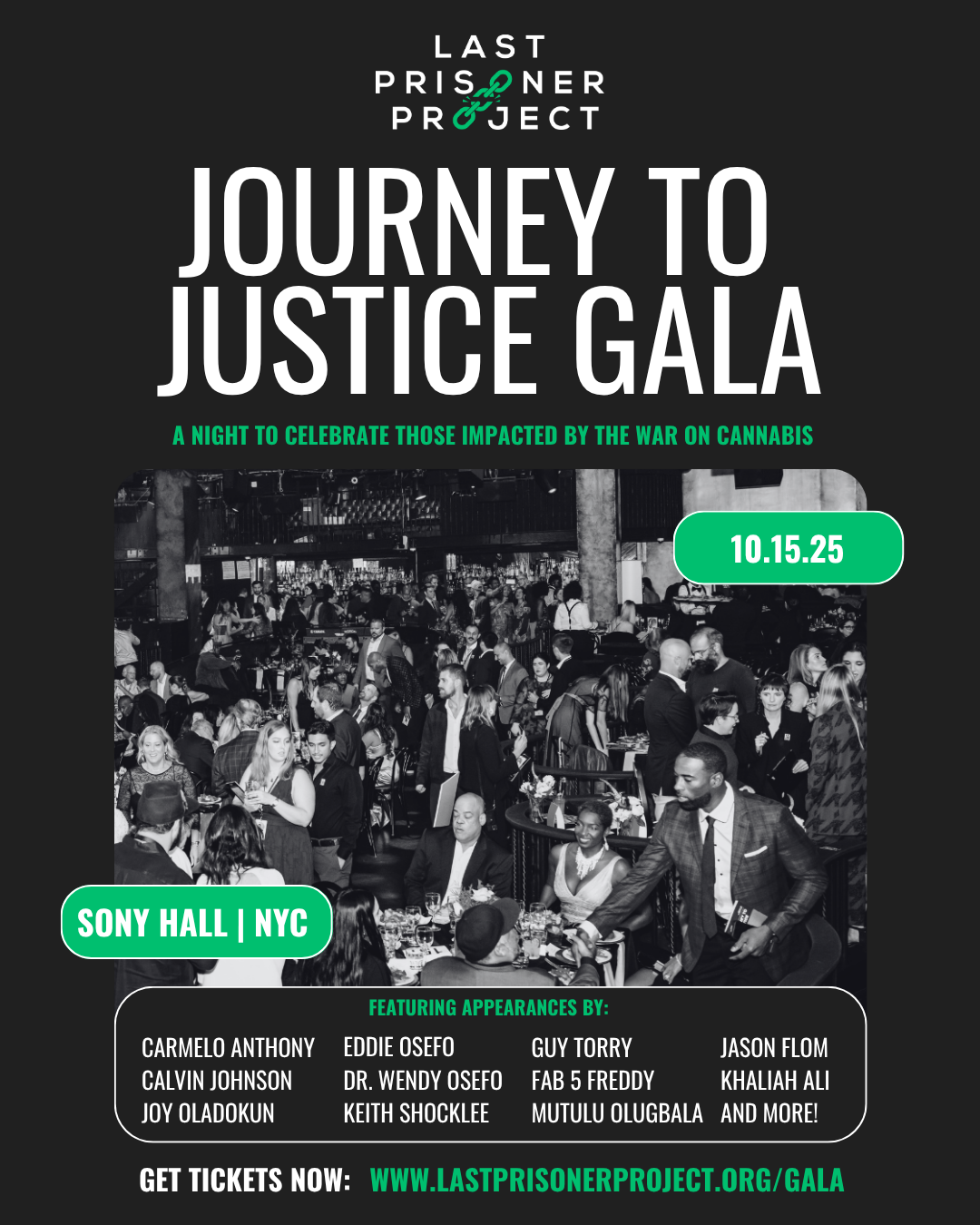

An interview with Last Prisoner Project’s (LPP) Director of Advocacy, Stephanie Shepard, and Amber Davidson of Cannifest. Cannifest will be taking place on September 7th-8th.

In today’s world, where the cannabis industry continues to evolve and challenge the long-time criminalization of cannabis, the stories of those who have had to navigate its harms offer a side that most don't get to see. As a cannabis felon myself, speaking with someone who knows what serving prison time for cannabis feels like, what type of impact it has, and how moving forward is possible; it always feels like a safe space. I was honored to delve into the remarkable journey of Amber Davidson, a former cannabis prisoner who is transforming adversity into acceptance and advocacy. Amber sheds light on the challenges of navigating the system, the impact of probation, and the driving force behind her determination to reclaim her spot in the industry that she helped create as a legacy grower.

Stephanie: Amber, can you share a bit about your background and how you became involved in the cannabis industry?

Amber: I started smoking weed when I was 14. It was one of those moments where I wondered if I was doing something wrong, or if was I just trying it because it was not what my parents wanted me to do, but I realized that I was just trying to find my community. Being with people who also smoked weed felt like I had found them. I got jumped a few times when I was younger, so I had difficulty fitting in with people from middle school through high school, especially high school. When I changed schools, being the new kid was difficult. And I just started building community through cannabis. One of my boyfriends at the time was very involved in cannabis, and so for me, it was finding that.

Stephanie:

How would you describe those people? What were the characteristics of the people that you found accepted you, and made you feel safe and comfortable in that circle?

Amber:

We were the people who hung out under the bleachers. We were the ones that didn't fit in with the general groups of people. It was funny because this group was made up of people from different circles. Athletes, artists, and musicians were all brought together by cannabis but also felt like black sheep because of cannabis.

Stephanie:

So even back then, the stigma surrounding cannabis was very prevalent. Does it surprise you now to see the lengthy sentences that victimless cannabis prisoners are still serving all these years later?

Amber:

It's very disheartening to see people still getting in trouble and still serving these insane sentences, and others are afforded the luxury to make careers stemming from the plant. Even myself and others who've been negatively impacted by cannabis criminalization are now able to viably see this as a career opportunity, and it's just mind-blowing that the system holds different people to different standards.

Stephanie:

When you think of Michael Woods (serving life), Parker Coleman (serving 60 years), or Jason Brant Gregg (serving 15 years), do you feel a sense of guilt that you came from the legacy market like them but are now free to openly participate in the legal market?

Amber:

To be honest, it does make me feel guilty because it's difficult to process being on the outside while all of these people have been in for so long for the same plant.

Thinking of people who have committed much more heinous crimes, actual crimes, who get an equal or lesser sentence, it's a hard pill to swallow.

Stephanie:

You served 49 months of a 70-month federal sentence for cannabis. We served time at the same facility in Dublin, California. How did those 49 months impact you and your relationship with your friends and family?

Amber:

I have a very small family. Both my parents were adopted, so I didn't have a lot of the same familial support that a lot of other people had, then and now. My dad passed away when I was in my mid-twenties, and 6 months to the day after I was raided, my mom passed away. Trying to navigate all of it, essentially alone was fucking difficult. I had some step-family, but after my dad died I didn’t feel like a family anymore per se. It felt like “Okay, we'll be here to take your phone calls and send you letters”, but I didn't have a courtroom full of people there to support me.

Stephanie:

Having that support helps you get through the experience. Do you feel like you leaned more on friends, or did you just feel like “I'm in this alone?”

Amber:

I leaned on friends a lot. I only had a couple who felt comfortable communicating with me during everything. I had one girlfriend, Beth, who offered me a job immediately when I got out, and she was a new friend. She was somebody that I had met when she was helping my ex-boyfriend get his accounting in order for his business before we got in trouble, and so I barely knew her. I may have known her for 7 or 8 months before we got in trouble, as strictly a business relationship.

She ended up being one of the only people who would regularly visit and write to me all the time. She took my call every time I called her and always made sure to email me and send me letters, cards, or pictures. We call each other sisters. There's a reason why we came into each other's lives at the time that we did. I know why she came into my life because I needed her. It's been such a powerful friendship because of that. She just saw that I needed a friend and very rarely do people show up that way. One thing I will say about cannabis, in general, is that I’ve found a lot of people in the industry who just want to be good, want to be friends, and be a good friend to people.

Stephanie:

You made it through that chapter, you got out, but you did a little bit of probation time. How long were you on probation? Can you tell me a little bit about what it was like to navigate life while you were on probation?

Amber:

I was on probation for about about 2 years. I treated probation like I was on home confinement, but a much more free home confinement. I couldn't leave certain areas. I couldn't go to Sacramento, Tahoe, or L.A. I got in trouble once for something that I shouldn't have been doing, I fucked up and failed a drug test. I remember profusely apologizing and crying my eyes out. I was terrified and decided at that moment that nothing was worth that feeling.

Stephanie:

What was your biggest fear? Were you afraid of the interruption it was going to cause in your life after all the time you had put into your reentry?

Amber:

I was afraid that I was gonna lose all of my good time, be violated, and go back! I had to drive to see my probation officer after I knew I had failed the drug test, knowing that's why I was going there, and in fear as I was walking into her office in the Federal Courthouse buildings. There were agents of all types, including U.S Marshals, that I knew were going to be waiting for me when I walked in the door. While I was sitting there with her, I just kept thinking they were going to come in the door and arrest me. Thankfully, that never happened. But, oh, my God! Was I terrified? Scared straight for sure. There are some things that I took away from prison that weren't entirely bad.

Stephanie:

What lessons did you learn what lessons did you learn from your overall experiences that personally and professionally stick with you today?

Amber Davidson: One of the biggest lessons I learned is nobody's going to come save you. You have to figure it out for yourself and be okay with whatever decision it is that you make. For that to happen to me, there was a period where my ex-boyfriend was firing attorneys left and right, hiring new ones, and he did the same to my attorneys or convinced me to do the same to my attorneys. There were a lot of things that I should have done differently, but I know that the decisions that I made were based on the information that I had at the time, so I'm okay with those decisions now. For me, being okay with myself and the decisions that I made. Even in this situation, I just had to ask myself “What will I do moving forward? And how do I make the best out of it?”

Stephanie:

You are now a leader in the legal cannabis space, what advice do you have for others who may have faced similar challenges and are looking to move forward as you have?

Amber Davidson:

The most frequent question that I was getting asked as I was deciding to get into the legal cannabis industry was, “What do you want to do?” It took me a while to figure out what it was that I wanted to do. The one thing that I did know was that I deserved a space here. I'm supposed to be here. It took me honing in on what it is that I wanted to do to be able to say, ”This is how I'm going to move forward.” When I began defining what that looked like, more opportunities started coming to me, even from the same people who were already asking me “What do you want to do?”

Stephanie:

That makes all the sense in the world. And that is a great first question to ask yourself. When we get out and see what the market looks like for some, we want to dive head-first into it without having the tools to make it happen and that can be incredibly frustrating.

Amber Davidson:

Specifically for somebody who is in the same position that we’re in as a felon. I just recently got my dream job working with Cannifest, a 2-day music and cannabis festival in Humboldt County, but it took me having to interview with several places, like the local casino, where I got a big, fat “Unless you can get your felony expunged, absolutely not!” It was very disheartening. I don't know if it's because as soon as you Google my name, my case comes up, but once I found what it is that I wanted to do, I started even getting real interviews with people who were ready to go to the next step, but then having to have that conversation with people that are not in the cannabis industry, and saying “...so I do have a felony.” I had to practice having that conversation. Figuring out how I was going to portray what happened to me, and what were the events of my story that I'm willing to share with people. Coming to terms with how it may be received. Figuring that out is probably one of the best pieces of advice I can give.

Stephanie:

With all that you have experienced, how have those experiences motivated you to be an advocate for reform?

Amber Davidson:

It's really hard to see people sitting in a place that I once was and didn't have the support that exists today. It's really important to amplify everyone else's mission like LPP or other organizations that are trying to do good by trying to be that bridge and include as many people within the cannabis industry as possible. It's unfathomable to me how LPP can support so many people when we look at how many people are still incarcerated. In all of the different ways, you know whether it be helping them find attorneys, helping them get back on their feet when they get out, helping their families while they're in, making sure that people are getting letters and being remembered and talked about. It's really important to me to also amplify that message for everybody because bridging the gap between people who are in the industry today that even acknowledge that this is a reality, which a lot of people don't even want to acknowledge. That's my main advocacy goal.

Stephanie:

How do you think that your background and your experiences help influence the public perception of cannabis, and what a cannabis “criminal” looks like?

Amber Davidson:

I've been hopeful and getting more comfortable being the face of the idea that I could be your sister, daughter, or wife. Sometimes it's a little bit disheartening because some people don't see it as that. They're just like “Okay, cool. You got in trouble. That's not gonna happen to me.” A lot of people don't think of it as being a real reality because of the way that the laws are in each State. It's easy to live in your bubble and forget that our experience is still a very real possibility for anyone.

Stephanie:

That's one of the challenges I feel like I encounter a lot, people feeling like it's so safe and forgetting that it's federally illegal. The normalization of cannabis is great, but I fear it will become so normalized that people forget about the tens of thousands incarcerated.

Amber Davidson:

My goal is not to scare people but to remind them that the plant is still under siege by many people. Many people have put themselves out there in social media land, trying to amplify their voice or their brand, and in turn, ended up getting caught in the crosshairs over a variety of things, but unless we keep talking about it, how will others ever learn?

Stephanie:

I couldn't imagine if all of the advocates just stopped talking about it. If there was no LPP, no Free My Weedman. I know what not being fought for feels like and I can't imagine not being the voice that I didn't have serving my 10-year sentence. If you had one message for outgoing President Biden, the incoming new administration, or state governors, what would that message be? How can they right the wrongs of cannabis criminalization?

Amber Davidson:

I think there needs to be a better understanding of the disparities in the types of crimes and the types of sentences that are being given right now, the punishments do not fit the “crimes” 99% of the time. I don't know if there's a way to right this wrong. If they decide to deschedule things or reschedule things, what we did is no longer considered a crime. There is no making things right for us, but they can start with the release of currently incarcerated cannabis prisoners, that is a given, then really taking a look at moving forward and not treating cultivators and distributors like we had bad intentions with what we were doing.

Stephanie:

Thank you so much for taking the time to speak with me, Amber. I don't think people hear enough from the women who have had these experiences. Your voice is incredibly valuable. Thank you for your advocacy, your work in the space, and for bringing Cannifest to Humboldt!